As we announced in a first introductory text (https://www.fundacionjacobea.org/en/santiago-of-compostela/the-book-of-santiago-introduction-to-the-codex-calixtinus/), we wish to devote our attention to studying the Calixtinus Codex (Liber Sancti Jacobi) in depth, advancing through its five books and addendum, but also through some particular figures and themes, which will allow us to examine the complex and rich medieval world. Today we approach the first of the books of the codex through a fundamental topic: music.

Book I – by far the longest of those that make up the codex – it is a compilation of documentation on the cult of Santiago, of the materials necessary for the liturgy of the cathedral, particularly for the celebration of the main festivities of the Apostle Santiago. The importance of music for this medieval liturgy was enormous, even more so at the time when the Calixtinus was compiled in the first decades of the 12th century – since the Hispanic churches had only recently adopted the new Roman reform and new ones were needed for rituals and songs.

Despite what has been said, it is important to emphasize that authors such as Díaz y Díaz or great experts in medieval music such as Ismael Fernández de la Cuesta, have pointed out that Liber Sancti Jacobi would not have been created as a simple direct reference book to follow throughout of the year in the church, but with the object of its being a guide or directory. This character of reference fits in better with the musical treasures that it contains, since, far from being limited to the music for the most important festivities contained in its Book I, its addendum also includes numerous songs, polyphonic “conduits”, which in their time must have been sung in various churches, monasteries and even on roads in Europe.

The structure of Book I of the codex is simple: a series of sermons by ecclesiastical authors relating to the most celebrated festivities in relation to the Apostle James: the festival of his Martyrdom, which is celebrated on July 25; the festival of Miracles, which is celebrated on October 3; and the festival of the Transfer of his body to Galicia, which is celebrated on December 30. There are also other more practical texts that seem to function as guides for the liturgy, but fundamentally Book I is dedicated to the three festivities mentioned, as well as prayers and songs for the various offices or prayers of the day.

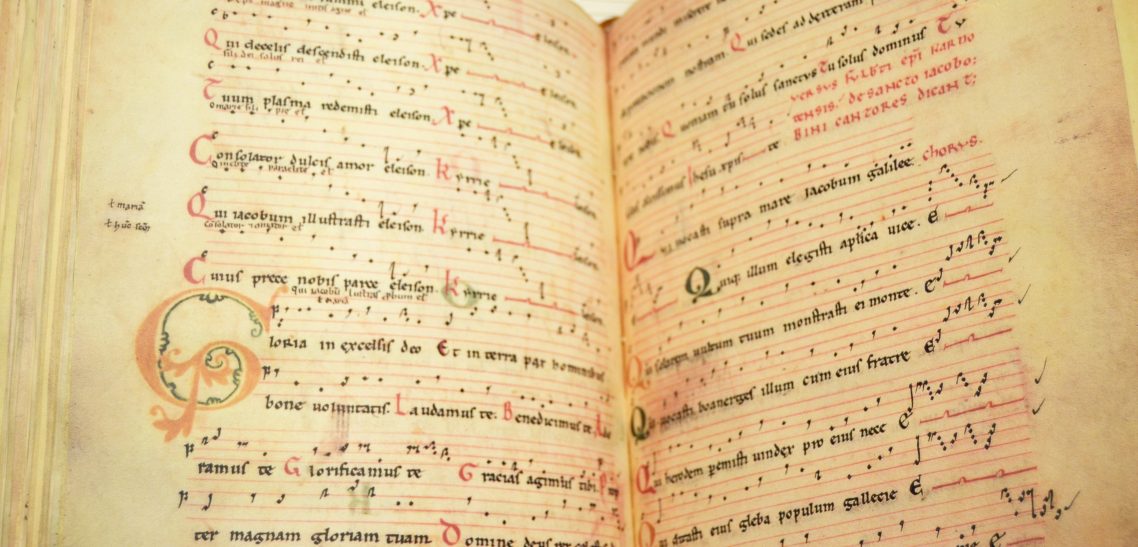

The scores, which are added from chapter XXI, are pages with musical notation, in this case according to experts, a notation closer to the French one than to the Visigothic one that until then had been in force in Spain. These scores contain the songs for the service and the masses, that is, the songs necessary for the services and the various masses of the aforementioned festivities. At this point, we consider it important to remind today’s reader what the offices meant in the Middle Ages, they meant prayers and songs for the various hours of the day scheduled according to the monastic rite under certain names: Matins (before dawn), Lauds (at dawn), Prima (first hour after dawn, around 6:00), Tercia (third hour after dawn, around 9:00), Sexta (the nap derives from it, around 12:00), Nona ( around 3:00 p.m.), Vespers (after sunset, around 4:00 p.m.) and Compline (before the night’s rest, around 9:00 p.m.).

From what has been mentioned, we could summarize the musical content of Book I of the Calixtino as a work of great magnitude that includes all the songs necessary for the hours or offices, the votive mass of the pilgrims and the special masses celebrated on the occasion of Miracles. , Martyrdom and Translation.

And finally, we can get a little closer to those songs, to their form: we find antiphons, responsories, psalms and nocturnes, the characteristic works of the Roman liturgy or office that Spain was adopting. However, as the aforementioned Fernández de la Cuesta has pointed out, the liturgical proposal of the Calixtino Codex is still in some way a mixture between music and the monastic rite and the new Roman liturgy.