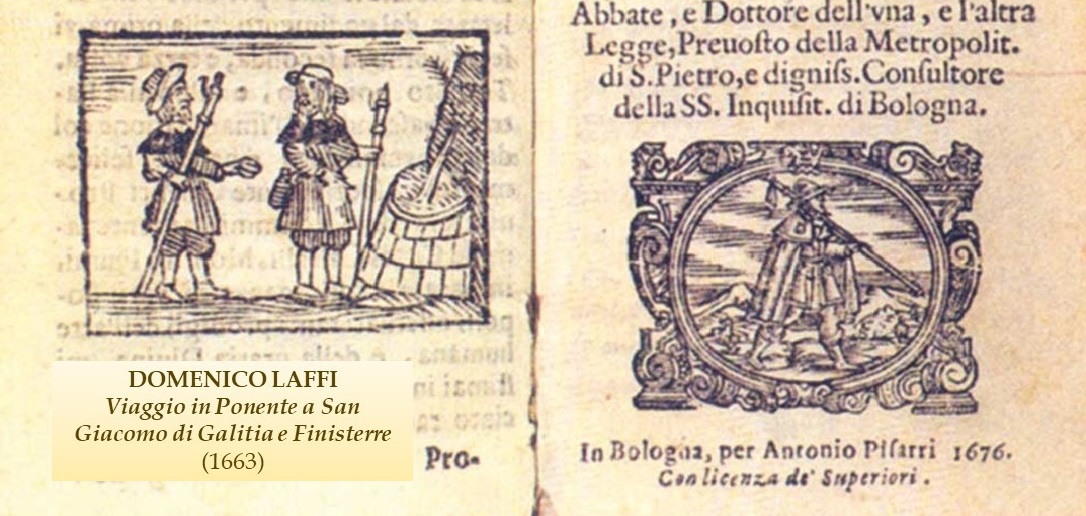

Domenico Laffi was an Italian clergyman originally from the 17th century city of Bologna, a pilgrim to Compostela on several occasions and the author of an extraordinary account of his pilgrimages published and republished numerous times over the centuries.

Through his stories, we know that Laffi made a pilgrimage to Santiago on at least four occasions: in the years 1666, 1670, 1673 and 1691. It was on the occasion of his second pilgrimage that he decided to write his detailed itinerary under the title Viaggio in Ponente. to San Giacomo di Galitia e Finisterre per Francia e Spagna, published for the first time in Italy in 1673. Through his story we learn what the pilgrims of that time -and we could also say of previous centuries- used to do along the Camino: their particular Visitandum Est , that is, how they followed an itinerary drawn from visiting towns and sanctuaries, marked by the existence of a reception infrastructure and the presence of relics, cults and devotions. In the specific case of Laffi, his long pilgrimage to the west led him to visit the lands of Italy, France, Spain and Portugal.

Laffi was a pilgrim from the 17th century, a time in which wars, plagues and religious schisms had led the Camino de Santiago to a certain decline. His first pilgrimage began in 1670, in the city of Bologna, and he undertook it together with the painter and personal friend Domenico Codici. They followed in the footsteps of many Italians -because the nationals of this country had never stopped making pilgrimages to Compostela- and they wanted to visit the tomb of the Apostle Santiago, which the Italians always linked in their stories about going west, to Finisterre where the sun shines.

Laffi’s account of the pilgrimage is key document because it became the classic itinerary that most of his compatriots followed for centuries to come: crossing Italy and part of France through the Via Francigena of pilgrimage to Rome -a route travelled throughout the centuries by pilgrims, merchants and crusaders- and later covering part of the Via Tolosana of the Camino de Santiago, the French Way to Compostela and then, continuing on from the city of the Apostle to Fisterra.

Following as far as possible the Via Francigena, Laffi and Codici ascended from Bologna to Parma, Piacenza and Milan. They then continued through France, visiting Avignon and later, Nimes, joining the Via Tolosana, one of the four great French itineraries of the Camino de Santiago. Through this Compostela route, the pilgrims continued their journey passing through Carcassonne and crossed the Pyrenees by the Navarrese branch of Roncesvalles, which they preferred to the then equally well-known Aragonese branch of Somport. From Roncesvalles, Laffi and his companion followed the classic itinerary of the French Way, as it appears in the fifth book of the Calixtino Codex.

Laffi’s extraordinary story offers multiple notes on everything he encountered on his pilgrimages: he refers to the importance of encounters with other pilgrims, how staying together was a tactic adopted in order to avoid the dangers of the Camino. He remembers the hardships and problems the pilgrim faced, from getting room and board to confronting bandits and disease He denounces the abuses of some innkeepers, but is also grateful to others for their good services and the attention he received. He describes the landscapes, towns and cities that he passes through; and as an ethnographer or anthropologist he notes different types of behaviour, clothing, customs, traditions, dances, games, rituals and liturgies. Concerning these rituals and liturgies, we would draw attention to Laffi’s descriptions and notes on Charlemagne, Bishop Turpin and the numerous legends and traditions linked to Orlando and Roldán; also his description of the most famous miracles of the Camino, such as that of the hanged pilgrim or the rooster and the hen in Santo Domingo de la Calzada and the famous Eucharistic miracle of O Cebreiro.

His arrival in Santiago is particularly interesting for us because it contains one of the best descriptions of the immense emotion that the pilgrims experienced when they arrived at Monte do Gozo. When from there they saw the city and the towers of the cathedral for the first time: “We discovered Santiago the place we had so longed for and shouted about so much. It was about half a league distant, and we fell on our knees, and tears of great joy gushed from our eyes, and we began to sing the Te Deum; but only two or three verses were sung, and no more, since we could hardly utter a word due to the abundant tears that flowed with such compassion that the heart trembled and the continuous sobbing made the singing stop”.

Finally, it is to him that we owe a rich description of the city of Santiago and the rituals that were then practiced in the cathedral, among them the embrace of the Apostle, as well as many other religious festivities that the city celebrated, such as a procession in honour of the pilgrim queen Saint Elizabeth of Portugal. After staying for days in Compostela, a city he refers to as “beautiful and big”, Laffi and his companion continued on their way to Fisterra and completed their Jacobean journey by visiting the town of Padrón, which over the centuries was recognized by the pilgrims as a ‘Jacobean place’.

After this journey, on his return to Italy, Laffi made numerous detours that, more than just due to devotion, seem to indicate his inexhaustible curiosity and spirit of adventure: he visited the main cities of Spain, such as Madrid and Barcelona, the latter city from which he returned to his home.

Laffi made a pilgrimage to Santiago four times, but he also made other pilgrimages, leaving written accounts of the ones he made to Jerusalem and Lisbon. We are especially interested in his pilgrimage to Lisbon, made in 1691 from Santiago, after completing his fourth Camino, in order to see the birthplace of Saint Anthony of Padua, a Franciscan saint who lived and died in Italy but was born in the Portuguese capital. The route chosen by Laffi to descend to Lisbon was the historical itinerary of the Portuguese Way, the pilgrimage route that we currently know as the Central Portuguese Way.

Laffi’s pilgrimage accounts were printed on several occasions, achieving great success during the author’s own lifetime and becoming a classic reference for many Italian pilgrims, to the point that the Viaggio a Poniente was the text used by Paolo Caucci von Saucken in the years 1960/70, when he began to make a pilgrimage and to study the Camino that, largely thanks to him, led to the development of other experts and the arrival of so many pilgrims a few years later.